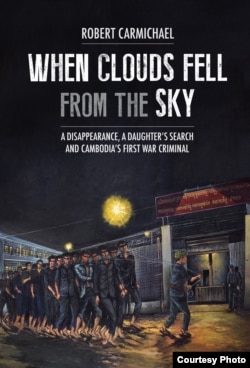

Editor’s note: The Khmer Rouge took over Cambodia 40 years ago, beginning one of the worst mass atrocities of the 20th century. South African journalist Robert Carmichael has covered Cambodia for many years and has just published a book looking at the effects of the regime on survivors, particularly those who lost loved ones. The book, “When Clouds Fell From the Sky,” charts the lives of five Cambodians, as a family waits to hear word from a lost loved one, and then, decades later, seeks some sort of closure through the process of the UN-backed Khmer Rouge tribunal. Carmichael recently spoke to VOA Khmer’s Neou Vannarin, in Phnom Penh.

What is your book about?

Well, as you say, this month is the 40th anniversary of the fall of Phenom Penh, and my book has just been released. And, the book is looking at the causes of the Khmer Rouge’s rise to power and the consequences of that, which were of course terrible as your listeners will know. And the way I’ve gone about crafting that story is to take the lives of five people and tell their lives through this period. So we have the lives of the five people in this period of Cambodia’s very turbulent, late 20th-century history and the effect that this regime had on their lives. So, that’s basically the structure of it: the causes and consequences of the rise of the Khmer Rouge and the effect that it had on these five people’s lives.

Of a person granted a scholarship abroad?

So, the man you’re referring to there is a man called Ouk Ket. He was from Phnom Penh. He won a scholarship to study in Paris as a lot of bright young Cambodians did in the ‘50s and ‘60s. The French government awarded him a scholarship. He went to Paris in 1968 to study statistical engineering, and he met, while he was in Paris studying, he met a young French woman called Martine, who is part of the book, as well. And they fell in love. They got married. And then Ket, himself, was posted to the embassy, the Cambodian embassy, in Senegal. And he and Martine moved there. They had two children in Senegal, and then in 1977 he was still at the embassy in Senegal, and the foreign ministry in Phnom Penh recalled him, saying he must come back to Cambodia to better fulfill his responsibilities. And so he left his wife, his young wife and two very young children behind in Paris and got on a plane. The plane went to first Karachi in Pakistan. He sent them a postcard from there. Then he went to Beijing in China. He sent them a postcard from there, saying, I’ll be in touch once I know what the government wants me to do, this being the Khmer Rouge government, of course, at this stage. Got on the plane in Beijing. Flew to Phnom Penh, and they never heard from him again. And so his wife spent several years trying to find out what had happened to him, and then decades trying to get some sort of justice for what had happened to him. As, indeed, did his daughter Neary, who is also, who is in fact the main part, the main sort of crux of the story is Neary.

How did you meet the people in your book, and why did you write about Khmer Rouge?

I should start by saying I was in Cambodia from 2001 to 2003, and at that time I was the managing editor of the Phnom Penh Post newspaper. And then I left in 2003, and I returned in beginning of 2009, because I wanted to cover the trial of Comrade Duch, the man who used to run S-21, which is now the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. The link between Duch and the book is that this young diplomat, Ouk Ket, when he returned in 1977, we know now that he was taken within a few days to S-21. He was held there as a prisoner for nearly six months, we assume tortured and interrogated, and then killed. So, when I met, when I came back in early 2009, I met quite by accident Martine and her daughter, Neary. They were here because they were civil parties at the Khmer Rouge tribunal because her husband, Martine’s husband, Neary’s father, had been killed at S-21. So they came here to see the start of Duch’s trial. And then during 2009, they came back several times to testify against Duch as to the effect that Ket’s disappearance and fate had had on them, and then later for the last week of trial. And the following year, 2010, they came back to listen to the verdict. So, they returned to Cambodia from France several times. And, that’s how they’re all connected.

Why did you write the book about the Khmer Rouge and the tribunal?

I’ve tried to write a book that will appeal, that’ll be of interest, to people living overseas. What happened in Cambodia in that less-than-four-year period is not widely understood internationally. It should be far better understood, because what happened was terribly important in terms of political systems that end up killing so many of their own people. And it’s not just Cambodia that we’ve seen it. We’ve seen it in China. We’ve seen it in Rwanda. We’ve seen it in other parts of the world, but that Cambodian experience is not as well understood as it should be. So from a broad perspective, I wanted to write a book that would try and address that.

From an individual perspective, when I spoke to Martine and Neary about their loved one’s disappearance and loss. They are both French, they’ve never lived in Cambodia, but their story of disappearance and loss and the damage it did to their lives is very similar to what happened to so many countless, hundreds of thousands, probably, millions of Cambodians. Where loved ones disappeared and we assumed they were killed, but there’s no body, there’s no proof. There’s just an assumption that that’s what happened to them. And that’s very damaging psychologically to people. Psychologists call this ambiguous loss. Where there’s just a chance in the back of your mind, a hope, that maybe your loved one isn’t dead and maybe they will one day come back. They won’t. I mean, the chance is.

In Ket’s case, Martine’s husband, we know now he was killed, and there’s no chance of him coming back. But for many years after he disappeared and when he came back in 1977, for many years, they hoped and hoped and hoped that what they’d heard had happened was not in fact true. And, it wasn’t until years later that they really got the proof they needed to find out, to learn what had happened to him. So I felt that two French people so deeply involved in the Cambodian experience would provide a bridge for people in the West, in the United States, in Canada, in the UK, in Australia who don’t necessarily know much about Cambodia. They know more about France than they do about Cambodia. And this is a way for them to bridge into the tragedy of Cambodia. And, then other members of Ket’s family in the book also make an appearance to describe what happened to ordinary Cambodians in that period.

My family has experienced similar loss and longing for disappeared loved ones.

And this is very common to situations around the world where this happens, whether it’s South America or Europe. It’s common to humanity. This hope that people we assume are dead will one day come back into our lives. And it’s very corrosive. It’s very psychologically destructive because, really, you know they aren’t going to come back, but you can’t help but hope they will. And so there’s no finality. No point where you can go, all right that person’s definitely, definitely dead. That person’s not coming back. The door is always possibly open.

Can you give us a recent update on the Khmer Rouge tribunal?

When I came back in 2009, specifically to follow the case of Duch, which was Case 001. And that was the case I followed most closely, because actually during a fair amount of Case 2 I was writing the book. I did follow some of Case 2. And, of course, as you say recently there have been movements in Cases 3 and 4. And, what we’ll have to see where those end up. I mean, briefly, Case 3 there is one Khmer Rouge defendant. Not defendant, yet. He’s not been charged, formally charged, anyway. But, there’s one person in Case 3 who’s still alive, and he’s now been technically, in terms of what the court does, they charged the person, that means their defense lawyers can then take a look at the case file. But a formal indictment comes somewhere down the road. And that’s what’s happened for three people in Case 3 and Case 4 is they’ve been charged with these appalling crimes, but that doesn’t mean there’ll be a case against them yet. What is does do is allow the defense lawyers to look at the case file and then to make their own submissions about their client and after that point the investigating judges will then recommend for prosecution or they’ll recommend the charges be dropped. That’s how it’s meant to work.

In Duch’s case, that was for me, and I think sadly for most of the media, was the most interesting case because this was the first Khmer Rouge cadre put on trial. And, the media, as you and I both know, loves the first, the biggest, the smallest, the worst – that’s what the media goes for. But, you know, going out and covering Duch’s trial in the first couple of days everyone comes in from overseas – the BBC, Al Jazeera, CNN, plus everyone comes to cover it the first few days and then everyone disappears. And, it’s just the local journalists like me, like you, the people who are living here covering it that actually end up writing the stories. And, even then if you’re dealing with an international audience that interest drops off quite fast. So, a lot of Duch’s trial was not well known internationally. And, that’s been the case, the situation with Case 2, as well, against Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, is that a lot of what’s happening out there is not being covered internationally. It is being covered in Cambodian media, which is good, but it strikes me as a shame there’s such limited interest what’s really one of the most significant stories of the 20th century in the world, yet looking at the international coverage of it, you’d be hard pressed to think it was really all that important, which it was.

Which again is why, going back to why I’ve written this book, it’s because that message, I think, needs to get out there. People ought to understand what happened here and why these things happened. That’s the most important thing. Why did they happen? Because if we know why these things happened, then in our other societies around the world, we can take steps. When we see things are going in the wrong direction, as they did under the Khmer Rouge – totalitarian, paranoid leaders, the individual has no worth at all, everything is a collective, all you’re useful for is the work we can get out of you, and if we think you’re an enemy we kill you. These are all degrees along a transition, along a plane, from tolerance to intolerance. And all societies have this plane, this transition. So we can see societies going the wrong direction. We can learn from what happened to Cambodia and we can ensure that won’t happen elsewhere.

To what extent can the tribunal help people reconcile the damage of the past?

I think it depends on the person. I think something like the Khmer Rouge, I mean, firstly, I’m a South African. I’m a white South African. And we had the apartheid government, which was very oppressive towards the black majority, and when that was overthrown 20 odd years ago now, South Africa put in place a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. And the purpose of that was to look at the crimes of that period of oppression and try and let people know the truth of what had happened and the way the groups on either side could reconcile, they could come closer together. That’s very different from a judicial process.

So what we have with the ECCC is we have a judicial process. And its job is not reconciliation, and I think there’s a misconception about what it’s there to do. The tribunal’s job, the judge’s job, is to look at the evidence against a very small number of people and determine whether those defendants are guilty of anything or not. And if they are, then it hands down a sentence. It isn’t concerned with reconciliation. That isn’t to say reconciliation can’t come out of it. I mean, in Martine and Neary’s case, for example, and other civil parties in Duch’s trial, too, of whom there were about 90 by the end of it, it is the case that some people felt that the burden had been lifted somewhat, that the weight of those years had been lifted somewhat.

But it’s important, I think, to make the point that the judicial process is not concerned with reconciliation. That’s a different process. And, that’s a process that is not happening in Cambodia, nearly as much as it ought to, in my opinion. And there are very few organizations doing it. There’s, as far as I know, zero government money going into it, which I think is a real missed opportunity, and is a real disappointment, actually, because there’s so much need for it. As Cambodians know, they will quite often be living close by to people who did appalling things, or may have done appalling things, or they think did appalling things during those times. And people simply don’t speak to each other for decades.

So this polarization goes on, and until organizations go in and try to bring about reconciliation. Nothing changes at that local level, and that’s where reconciliation has to happen, at the local level between people in the same village or in adjacent villages. Try and bring them together, try to let them see, yes, this man did take your father away, and yes he was killed, but then the survivors, the families of the victims, at least then have the opportunity to listen to the perpetrator and have him explain why he did these things, what his involvement was, how he feels about that today. And if people don’t speak, then there’s no way of finding that out. So I think the reconciliation thing is a different process. It’s extremely important, and unfortunately in Cambodia’s case, it’s largely not being done.

Mental health problems in Cambodia?

No help at all. I mean, the mental health budget in Cambodia is, even though this is a poor country, there is plenty of money being stolen by government officials. This is one of the most corrupt countries on Earth. It simply, to me is not credible that there isn’t money for mental health. And there’s such a need for it. Even just a few years ago I remember reading, maybe five years ago, the mental health budget was maybe $30,000 or $40,000, for the whole country for the year. That’s unacceptable. I mean, the number of officials driving around in $150,000 Range Rovers, clearly there’s money. There’s money. And, personally, I think it’s outrageous that there’s so little in a country that has so much psychological damage, so much post-traumatic stress disorder.

So many people saw such terrible things, or were involved in such terrible things. You know, violence like that damages the perpetrators as well as the victims. There’s simply, it simply isn’t good enough that there’s so little money going in. There’s more money going in now, but still far too little. And, we now know from… This is storing up problems for the future because we now know from psychologists that this damage goes down the generations. So, what parents, people, or grandparents survived the Khmer Rouge period saw, elements of that will get transmitted down to the next generation and the next in terms of behavior, in terms of how they deal with stressful situations. So, not dealing with it is actually storing up problems for the future generation, too. And, I for one would like to see much more money going into mental health issues in Cambodia, and into reconciliation because that’s how you rebuild society, and you try and make some sort of healing. The tribunal can’t do any of that, really. It’s not its function.

I mean, the government should be funding it. It’s the Cambodian people, and there’s plenty of money. Clearly there’s plenty of money being stolen. We know that. A little less could be stolen, perhaps. And that could go towards improving the health, mental health, schooling. There are all sorts of social issues in Cambodia that require better funding, and it is the case the government over the years has gone, “Well, the international community can do that.” I think the international community is getting a little tired, actually, of having to fund everything here. And it’s the government’s own people. They ought to be taking more care of them than they are, in my opinion.

Any second book?

I won’t be writing a second book about the Khmer Rouge tribunal. Honestly, writing that book was quite emotionally draining, because you interview a lot of people who’ve had the most appalling stories and it’s difficult. You know. It’s difficult to process all of this stuff satisfactorily. So my next book, I will write another book, it will be fiction. This one is nonfiction. So it’s all true. It’ll be a fiction book. That won’t happen for quite a while. I mean, I’m getting back to journalism now. So, as you know I report for VOA English Service, doing radio and television out of Cambodia. I’ll be getting back into doing the journalism, which I’ve somewhat neglected as I’ve been writing the book. So spending much of the rest of the year doing journalism and reporting on the issues that affect Cambodia, including reconciliation, health, mental health, politics, economics, all these things that you, your colleagues and myself sort of cover on a regular basis.