In August 1969, the United States reopened its embassy in Phnom Penh, restoring bilateral ties between the two countries, four years after a diplomatic cut-off initiated by the Cambodian government led by the late King Norodom Sihanouk.

At the time, King Sihanouk had taken umbrage to U.S. and Vietnamese incursions in southern Cambodia, on account of the widening reach of the Vietnam War, and concerns over growing U.S. influence in the Cambodian armed forces.

These, or similar, concerns surrounding U.S. involvement in Cambodia’s internal affairs would be used as a nationalistic rallying point by Hun Sen’s government in recent years.

Exactly 50 years later, the two countries – again – are seen seeking to mend strained ties, though this time around not so much a resumption of diplomatic relations, but more a reset of frayed relations.

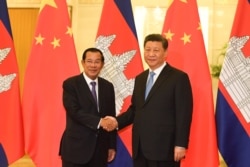

The cause of the most recent diplomatic slump was twofold: Cambodia’s increasing proximity to China and Phnom Penh’s assertion that the U.S. was aiding in a so-called “color revolution.”

U.S. ambassador to Cambodia, W. Patrick Murphy, handed Prime Minister Hun Sen a letter from President Donald J. Trump on November 21. The letter, aside from diplomatic small talk, made an assurance that the U.S. would not seek regime change in Cambodia – clearly an attempt to dispel paranoia among the political elite in Phnom Penh.

Hun Sen quickly wrote back welcoming Trump’s assurances and that his government wanted to “restore trust and confidence” with the U.S. He also thanked the Trump administration for “understanding” his government’s course of democratization.

The prime minister – and local media – seemed to ignore a key section of Trump’s letter, where he urges Hun Sen to move back to “democratic governance” and to “re-evaluate certain decisions” taken recently.

Exiled opposition leader Sam Rainsy, who was prevented from returning to Cambodia last month, said the Cambodian government was only projecting the positive aspects of the Trump letter, but that U.S. was still insisting on restoration of democratic institutions.

“Hun Sen may try to portray the exchange of letters as a rapprochement, but the Chinese military base and Cambodia’s democracy are not [the] issues that the US administration is going to forget about,” he added.

But for regional observers, the letter indicated a turnaround for the U.S., where the charged rhetoric emanating from certain sections of Congress for the last two years were now met with a more mellow diplomatic gesture.

And for Hun Sen, years of casting aspersions at the U.S. and constant references at a so-called “color revolution” had been conveniently cast aside to sidestep any potential sanctions from the Western nation.

Using the carrot and stick analogy, analysts said there would possibly be more of the former going forward.

“This is a turning point in the new U.S. approach towards Cambodia,” said Po Sovinda, a doctoral candidate at Griffith University in Australia, despite the two countries having fundamental difference in opinions over Cambodia democratic progress and human rights record, he added.

“On the aspects of democracy, the two countries could not find a consensus yet,” Po Sovinda said in a phone.

The U.S. has been at the forefront, alongside the European Union, to hold Phnom Penh accountable over the recent political crackdown leading up to the 2018 national election, which saw Prime Minister Hun Sen return to office, and this time with every parliamentary seat occupied by Cambodian People’s Party lawmakers.

But the depth of the bilateral animosity long precedes the recent crackdown.

The widening gulf between Cambodia and Western countries coincided with its increasing bonhomie, and economic dependence, on China. And this started long before China’s more recent spike in investments directed at Cambodia.

Back in 2009, Phnom Penh sent back Uighur asylum seekers to China, prompting the U.S. to cut the supply of military equipment, which was soon supplemented by China. Cambodia has increasingly made clear its support of China’s stance on the hotly-contested South China Sea territorial dispute.

The annual Angkor Sentinel joint infantry exercises between the U.S. and Cambodia and other American-funded military programs have been postponed indefinitely since late 2016. Phnom Penh has frequently complained about the approximately $500 million in Vietnam War-era debt accumulated under the Lon Nol regime still owed to the superpower.

The biggest concern for the U.S. seemed to report that the Chinese were building a naval facility at the Ream Naval Base in southern Cambodia. Brigadier General Joel B. Vowell, Deputy Director for Strategic Planning and Policy at the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, even confirmed in August that Cambodia and China are proceeding on a base for China's navy in Preah Sihanouk province.

Po Sovinda said the growing list of concerns, especially the geopolitical implications of Cambodia’s pivot to China, has pushed the U.S. to re-engage with Phnom Penh.

“[T]he U.S. will never give up on Cambodia and will never leave it to China or any other [powerful] country, as Cambodia stands strategically important now in U.S. Indo-Pacific strategies,” he added.

Cambodia is also facing external economic pressure to course correct, especially from the United States and European Union. The government has publicly maintained that it was unperturbed by these developments and would weather any potential repercussions or sanctions.

In a 70-page preliminary report submitted to Cambodian government last month, the EU noted that “there exist serious and systematic violations” of civic and political rights in the Kingdom. Awaiting a Cambodian government response, the EU will soon ascertain if the ‘Everything But Arms’ trade scheme should be suspended.

In the U.S., the Democrat-led House of Representatives passed the Cambodia Democracy Act 2019, which is now in the hands of the Senate’s Foreign Affairs Committee for review. If passed and signed into law, it “directs the President to impose sanctions on individuals responsible for acts to undermine democracy in Cambodia, including acts that constituted serious human rights violations.”

Carlyle A. Thayer, an emeritus professor at the University of New South Wales, said the timing of the outreach shows that the U.S. was concerned the potential suspension of the EBA scheme will push Cambodia closer into China’s orbit.

This was easier to do now, Thayer added, because of the Trump administration’s ambivalence to concerns over Cambodia’s democratic backslide, as opposed to President Obama, who was more direct about expressing the need for corrective measures.

“The new U.S. rapprochement towards Cambodia, including a letter from President Trump inviting Hun Sen to the United States for an ASEAN summit, will be welcomed in Phnom Penh not least because it will bolster the legitimacy of the Hun Sen regime internationally and domestically,” he said.

“Cambodia is likely to respond favorably to U.S. military engagement activities for the same reason.”

But Cambodian political analyst Lao Monghay expressed “cautious optimism” over the diplomatic outreach, and said the two countries seemed to have their own end goals for the reconciliation.

“The U.S. wants Cambodia to achieve sovereign democracy, independent from China, while Cambodia only wants to build trust and confidence between the two governments in a bid evade sanctions,” Lao Monghay said in a phone call.

Path Kosal, a political scientist with the City University of New York, said, given the recent outreach from the U.S., Hun Sen would oscillate between “deference” and “resistance” to strategically deal with Western governments.

However, he said the tipping point for the U.S. would be the establishment of a Chinese naval base in Cambodia, and anything short of that would be handled more diplomatically by Washington.

“Historical records have shown that Prime Minister Hun Sen is a pragmatist, and I predict that he is likely to adopt flexible and evasive strategies to avoid harsh sanctions by the Western allies,” Path Kosal told VOA Khmer in an email.

While Cambodia’s geopolitical realignment has focused on Beijing, Phnom Penh is also seen as seeking to reassure its traditional ally, Vietnam, that its ties with China would not be a threat for Vietnam.

The Vietnamese have been wary of China’s increasing clout in the region, trying hard to re-assert its closeness with Phnom Penh. This would also give Hun Sen a window to assuage Vietnamese concerns, knowing well that his old ally could help soothe the impasse with the United States.

Path Kosal said the strengthening of traditional ties with Vietnamese communist leaders, with one eye on mending ties with the U.S., would likely be Hun Sen’s strategy.

“The ‘China factor’ can be a useful leverage for small states like Cambodia and Vietnam to maneuver their foreign relations in favor of their strategic interests,” he said.

“Cambodia and Vietnam can coordinate their foreign policy maneuverings…to get the great powers (the U.S. and China) to lunge in a particular direction and then take advantage of these less attentive and agile great powers to get what they want,” Path Kosal said.