In 1980, Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe, one of the world’s longest-serving rulers, won an election and became president of the country. During the post-independence era, he was known for leading the revolutionary movement to end white ownership of land and striving for racial reconciliation.

In 1985, Hun Sen of Cambodia, also one of the world's longest-serving rulers, became the prime minister of Cambodia in a new government installed by Vietnam. He was credited with leading a revolutionary force that ousted the Khmer Rouge regime and achieving economic growth after the devastation of war.

Both were labeled “strongmen” and kept a firm grip on power.

After 37 years in power, on November 21, Mugabe, who once vowed to remain in power until the age of 100, resigned from office after a week under house arrest following a coup led by his top generals.

“Thirty-seven years of rule means that no matter what leaders want and declare to their people—such as their demand to rule another decade—change is unavoidable. Change is the only constant.” Ear Sophal, Associate Professor of Diplomacy & World Affairs at Occidental College, said in an email.

Though both countries made international headlines in the same month. But changes are also happening in Cambodia. Hun Sen, after 32 years in power and vowing to remain for another 10 years, has dissolved his main opposition, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), also in November.

The self-exiled former opposition party leader, Sam Rainsy, posted on his Facebook page that next year’s election in Cambodia also sees the departure of a strongman.

“Cambodian will similarly celebrate the fall of dictator Hun Sen who has also been in power for more than 30 years. Like in Zimbabwe, the armed forces in Cambodia should side with the people and stop obeying orders from the dictator,” he wrote.

Ruling Cambodian People’s Party spokesman Sok Eysan quickly sent a message urging journalists to “not compare Zimbabwe to Cambodia”.

In an interview with VOA Khmer, Eysan rejected the idea of taking Zimbabwe as an example of regime change in Cambodia.

“Zimbabwe and Cambodia are as different as the sky and the land. Grandpa Mugabe is now 93 years old; and as the law of nature and the fact that he may not have the ability to perform well, he is destined to resign,” Eysan said, adding that “people do not care how long a particular leader rules as long as they live in a peace, political stability and well-being”.

The transition in Zimbabwe may not offer much in the way of lessons or inspiration for Cambodia's opposition, according to Alvin Chheng-Hin Lim, a research fellow with International Public Policy, a consultancy, and author of “Cambodia and the Politics of Aesthetics”. Rather than a popular uprising against autocracy, the transition was “due to a conflict within the top elite of the ruling party [ZANU-PF]” he added.

Prior to the coup by military intervention, Mugabe wanted his wife Grace to rule after him.

“The long-time [Vice President] Mnangagwa retained the loyalty of the key party members and more importantly, the military leadership which helped him oust Grace Mugabe from power,” Lim said in an email.

“The legitimacy of the [Zimbabwe] government will remain in question until new elections take place that are competitive, free and fair,” Sophal said. “Sound familiar?”

Both leaders, Hun Sen and Mugabe, have created a similar legacy, Paul Chambers, a lecturer at the College of ASEAN Community Studies, Naresuan University, in Thailand, said. “They spearheaded political transitions in their countries, also stabilized their countries out of civil war.”

“Both were allies of the Soviet Union during the Cold War and both outlived the Soviet Union. But since the Cold War, both turned to capitalist development strategies to bankroll their authoritarian personalist regimes," he added.

Fortunately, Chambers said, Cambodia has experienced “enormous economic growth while Zimbabwe was a basket case of economic underdevelopment”. Yet he also warned that “If Hun Sen's economic policies are unable to keep Cambodia's macro-economy buoyant, then he has a Mugabe future for sure.”

Besides being notorious for keeping a tight grip on governments which have been accused of human rights violations and corruption, the commonalities of both leaders’ failure extends to a poor healthcare system. Mugabe and Hun Sen frequently visited the same country, Singapore, to seek medical treatment, rather than seek treatment in their respective countries.

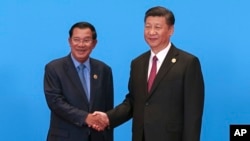

After more than three decades in power, Hun Sen has become one of Beijing’s most important allies in Southeast Asia. His government can count on China’s support for the upcoming 2018 election. With China’s financial support, which doesn’t attach conditions and pressure to value human rights and democracy, Hun Sen can safely ignore criticism from the west.

In Zimbabwe, Mnangagwa, who was sworn in as president this week, is also accused of the same pattern of human rights abuses and corruption as his predecessor.

“Indeed, if you had competitive, free, and fair elections, you could replace the person in charge and would not be stuck with a dictator. Let’s just hope ‘The Crocodile’ doesn’t rule for another 37 years and plunge the country deeper into the abyss,” said Sophal.