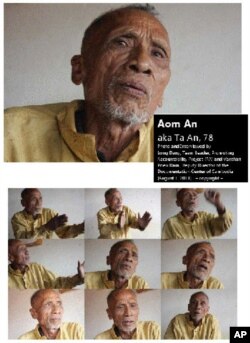

Editor’s note: Ta An is among three former Khmer Rouge cadre cited by prosecution at the UN-backed Khmer Rouge tribunal as suspects in Case 004. That case is currently with the office of the investigating judges, who must determine whether he and two others should be indicted. In an introductory submission to the court in November 2008, the UN prosecutor alleged Ta An’s involvement in purges of the Central Zone, where he had risen to deputy secretary, along with other atrocity crimes. He spoke to VOA Khmer in an interview at his wooden home in Battambang province’s Kamreang district, where he lives with his second wife and teenage daughter, growing corn, soybeans and bananas.

A few months ago, court documents were made public showing that you are a suspect of the tribunal. You have been implicated by the prosecution in the deaths of many people in Kampong Cham province. Do you have any comment on those allegations?

I don’t. I’d like to tell you that in Kampong Cham, I wasn’t involved in anything. For me, personally, when they sent me to Kampong Cham, there was chaos everywhere. When they sent me there, Kampong Cham didn’t have anybody in charge from the village level to the commune and the district. They removed everybody, and they cleaned everything up. I went to set up everything anew. I wasn’t involved in anything. I’m telling you the truth.

The prosecutor’s office says it wants to bring five more people to trial. On its list, your name is there. Do you have any objection to seeing your name on the prosecution’s list?

I don’t. I don’t have the right to complain. Like I said, I didn’t have any involvement in the killing. When I got there, there was nothing left, from the bottom to the top. There was only [Central Zone Secretary] Ke Pauk remaining. I began to set up new villages, new communes. How could I have been involved in anything? No.

When you went to Kampong Cham, there was already chaos? And there were people dying around that time?

Yes. They had already cleaned up, and I got there after the fact. It was already done, and I set up afterwards. There was only Ke Pauk left. I was not involved in any killing in villages, communes, districts and regions—and that’s what I object to. I had no involvement. Up to ’77, ’78, ’79, everything was gone. There was nothing left.

What role did Ke Pauk have at the time that it was only he who remained?

Regional secretary.

That means he centralized everything there?

Yes.

Then the charges that you were involved in the security apparatus were a misunderstanding on the part of the court? Why do you think there are allegations against you from the tribunal?

For that, I presume it was their misunderstanding, because I didn’t commit any crimes.

That means people were dead before or—

They removed them. The disorder had been removed completely. I don’t know where they were moved to. When I got there, they were gone. Only Ke Pauk remained, and I don’t know what Ke Pauk was in charge of at the time. I only know he was a regional committee chief. Of that regional committee, he was the only one left. I went not knowing about anything.

When I saw there was nothing left, I started to set up from the village level to that of the district. After the reorganization was finished, everything was back to normal. So nothing happened. There was no more killing. People started to work on irrigation dikes, canals and rice fields. When, in ’77, ’78, ’79, the government [faction] attacked, we fled to safety. I was there for not quite two years. Therefore I was not involved in anything. I don’t know what I was charged for. These are my facts.

There has already been an announcement that the prosecution wants to bring in five more people. Has anyone from the court contacted you or approached you with any inquiries?

No. No one.

During the struggle, why did you join the Khmer Rouge?

I want to tell you this: by tradition, I respect the king. It has been like this for generations, since my grandfather. And on March 18, 1970, His Excellency Lon Nol mounted a coup to overthrow the prince [Norodom Sihanouk]. Then there were big demonstrations everywhere, as the prince announced that all his children and grandchildren must flee to the border jungles to the resistance. This was the reason why, when the prince announced that he was head of a national united front, everyone joined the struggle.

So you must look at me. Look at the color of my skin. Do you think I have the ability to come up with such initiatives? No, I don’t. It doesn’t match with the leading of a struggle. And when in the end we achieved victory in 1975, we were all surprised. We raised the communist flag, and we were all surprised. But all in all, this was the unification of Cambodia under the front flag that had all along Prince Sihanouk as its leader. This is only my personal account.

How old were you when you joined the fighting? Why would you make such a sacrifice for Prince Sihanouk?

It was to protect the monarch. When the country had a monarch, and when His Excellency Lon Nol staged a coup, we as the people and [Sihanouk’s] grandchildren had to fight to put him back in power.

If the court brings more people to trial, are you afraid, or are you prepared to defend your case?

I don’t have any fear whatsoever. Because of what I just told you about the monarch. Obviously, I didn’t carry out any executions. Having said that, I’d like to add that during the fighting, from 1970, I carried a weapon. In fighting, you don’t know who will die and who will live, but after our victory, I didn’t commit any crimes, and that’s why I say I have no fear. But a [court] that seeks justice must provide justice. When you bring people to trial, you must provide justice. If I didn’t commit any crime, why bring me to trial?

Things only happened during His Excellency Lon Nol’s era. People shot at me; I shot at them. We fought each other to the death for the claim of Prince Sihanouk. After our victory, I didn’t carry out any killings. I only built dikes. And if building dikes is considered a violent act, I don’t know what to do. Is building dikes a fascist act? You tell me. We had a lot of dikes. In Kampot province, we built dikes at Prim Lich, Koh Sla, Sdok, Chhouk, Toan Hoann, Kbal Lmeas. Toan Haonn dike is located in Kampong Trach district, near Vinh Te canal on the Vietnamese border. I helped build dikes in many districts, such as Koh Sla, Prek Khnong, Touk Meas and Kampong Trach.

When the court summoned five former senior Khmer Rouge leaders—Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary, Khieu Samphan, Ieng Thirith and Duch—to trial, what were your views at the time? Were you concerned that other leaders like yourself would one day be tried?

I have no fear, as I told you.

But it is rather difficult to believe, with well-known leaders such as yourself and others working in an area where a lot of people were killed, that these leaders can deny involvement.

I don’t know who knows me [as well known]. But I’ve told you the facts. Most importantly, I saved many lives.

How?

Up to ’79, when the government attacked, I hid representatives that were sent. I hid them at the dike construction site, provided them three meals a day, and in the evening gave them palm sugar. When the government attacked, I ran to stay with the working groups for three days. Nobody did or said anything [to me]. Then I said, “Nephews, go home, go to Prey Veng,” people left, as well as people in other provinces, and I escaped too.

This is what I call a rescue. There was saving. But killing, executing, I don’t understand. When the region made arrests and sent the forces [people] to me, they were sent to be destroyed. They asked me, Ke Pauk asked me, “Where are the forces?” “Cleaned,” I told him, but they were on the farm. What should I have done more than that? What can I say, if I tried to hide people like that? So I am not frightened, not frightened at all. I do not remember their names, there were so many people.

In Kampong Cham, there were about 150,000 people killed, and in O Trau Kuon temple in Kang Meas district, there were more than 32,000 people killed. Do you know anything about that?

Where, O Trau Kuon?

Yes. The tribunal prosecutors said you were responsible for the O Trau Kuon temple area in Kang Meas district at the time.

No. I never knew anything about that. I don’t know where O Trau Kuon is located, and I don’t know who did the killing there. Perhaps people before me, I don’t know. I was there in ’77, so before that, I don’t know. But if it was in ’77, I don’t know who carried out the killings in O Takean or O Trau Kuon. There were no killings.

On another topic, I tell you honestly about when Ke Pauk was the chief. For the clean up operations, they asked this question: “How do we solve the April 17 people?” I said, “What do you mean, ‘How do we solve them?’ What did they do to us? What violations, what conspiracy did they commit?” Then they said, “If you don’t do it, we have the regional troops to do it.” And I said, “If the regional troops do it, then I’ll go home.” I simply said it like that. I said, “If I don’t do it, if I say I can’t be responsible, why should I stay? I’ll just go home.” This is the reason why I am not afraid.

After all this, if the court wants to put me on trial, well, go ahead. At present, I am not fearful of the court, and in the future, when I die, I won’t be afraid of Yama [Buddhist god of the dead]. Not fearful. I am now doing good deeds. I practice religious art. I did not commit killings. But am I afraid of Yama? I am not afraid.

Under the Khmer Rouge, there were so many people killed—almost 2 million people all over the country. What were the reasons?

I don’t know. It’s too deep for me to understand. It’s beyond my capacity, and I don’t know why.

What part of Kang Meas did you control?

I was in Prey Totoeung, and the people there loved me considerably. I was very surprised that when I went someplace, they all came to me. There was a time when they took down the house structures that belonged to the people and brought the pieces to be piled up at Prey Totoeung, to rebuild houses for the leaders. At the time, I even called a meeting to ask people to come take the columns back and build their own houses.

Talking about love, when I went to Kang Meas and to Kampong Siem, I brought palm sugar along. When they saw me, they yelled, “Sugar is here!” And when I came back from that direction, I brought tobacco in big bundles and distributed it at the dike construction sites, and people said, “We have tobacco.” No one ever said anything bad. So I’m surprised by the accusations.

But where did the orders to the lower levels to execute or kill someone come from?

No, there were never orders.

Does that mean that there were so many people killed that lower-level cadre did the killing at their own will? Or was there some behind-the-scene problem?

I said there were no orders, but there were instructions. Instructions were given when there were acts or activities against an issue. If there was no opposition, then even those designated the April 17 people would not have been killed. This is a fact. That’s why I don’t understand.

Would you be afraid if the court issues a warrant for you to appear?

No, I’m not afraid.

Would you go? Would you confront the court? Are you prepared to face the court?

Let’s talk about wants. No, I don’t want to, because I have a job to do to make a living. Do I want to go to the court? No, I don’t. Unlike Mr. Khieu Samphan, who said he wants to make an explanation to the court, I don’t want to. Firstly, does the court have a place of worship? Does the court have a place for me to say my prayers? I think it does not, so why would I want to go there? I don’t want to go, but I’m not afraid to go.

If they came to arrest five suspects—namely you, Meas Muth, Suo Met, Im Chaem and Ta Tith—what impact would this have on society as a whole or in your life?

It will affect my life for sure. Regarding society, I don’t know how to answer. I don’t know how this will have an affect on the national societal level, but it will affect my family life very much.

In what way?

Naturally, it will affect the way my family feels. As poor as we are, how will we solve this problem? Perhaps we’ll have to sell our land, because we have no more money. It will affect the children’s education and our daily life. That’s why I said I don’t want to go, but I am not afraid to go. I don’t want to go explain my case, but I am not afraid to go, because I did not carry out any killings, and the fighting was not of my own initiative—for which I lack the mental and physical ability.

I want to add another comment, because I’ve heard Prince Sihanouk explain that he was imprisoned during Pol Pot’s rule. So let’s consider Prince Sihanouk’s status and look at my own. What do you think?