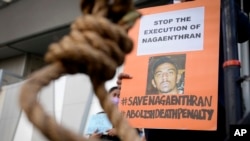

Rights groups say they welcome the Malaysian government’s announcement to end mandatory death sentencing but question whether lawmakers will follow through, having seen similar plans in the past fall flat.

Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar, the minister for law in the office of the prime minister, said in a statement Friday that the death penalty for the 11 crimes that now make the sentence mandatory would instead be meted out at the court’s discretion. He said the cabinet also agreed to study alternative sentences for those crimes, which include rape and murder.

Malaysia’s parliament will still have to pass amendments to several laws to make the cabinet’s pledge a reality. Wan Junaidi gave no indication of when the government would propose the requisite legislation.

The law minister did not answer multiple messages asking for comment.

Welcome but wary

Dobby Chew, executive coordinator of the Malaysia-based Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network, told VOA he was glad to hear of government’s plans but still “very cautious” about raising his hopes for change, having heard it before.

In 2018 the government of then-Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad announced plans to do away with the death sentence altogether. Facing vocal rebuke from the opposition, the government scaled back its ambitions to ending only mandatory death sentencing instead, then collapsed in early 2020 before putting any legislation to parliament.

Two of the opposition parties that campaigned hardest against abolishing capital punishment in 2018, the Malaysian Islamic Party and the Malaysian Chinese Association, are now part of the ruling coalition.

“So, I’m skeptical and concerned about that, but cautiously optimistic,” said Chew.

A spokesman for the Malaysian Islamic Party declined to comment. The Malaysian Chinese Association said its spokeswoman was not available.

Amnesty International, which wants to see the death penalty abolished worldwide, called Malaysia’s announcement “a step in the right direction” in a statement of its own Friday. It urged the government to send the necessary amendments to parliament “without delay.”

Like Amnesty, Chew said the amendments would be a helpful move toward the shared goal of scrapping the death penalty for good.

“At the most fundamental level there’s a moral belief on our part that ... if murder is wrong then we shouldn’t do it to someone else,” he said.

“And when we come to a country like Malaysia, on top of the moral concerns that we have on the use of the death penalty, there are concerns on the right to a fair trial, there are issues of torture in custody that lead to false confessions, and things of that like,” he added.

A 2018 study of nearly 300 capital punishment cases in Malaysia by the Penang Institute, a local think tank, concluded that the accused’s gender and nationality, the particular court conducting the trial, and the type of alleged crime were all contributing to “a high judicial error rate” and creating a “high probability of wrongful execution.”

Into the past

The government has not said whether the changes, if passed, could apply to prior sentences. But Friday’s announcement is kindling hope of commuted sentences among the families of the more than 1,300 people already on death row, or at least a better shot at clemency from Malaysia’s king.

In its statement, Amnesty urged the government to review all existing mandatory death penalty cases “with a view to commuting these sentences.”

In 2013, Chandra Segaran Senguttuwan drove a car into the outdoor banquet area of a wedding party in Gopeng, Perak state, killing an 18-month-old boy and injuring two others. Two years later, Malaysia’s High Court sentenced him to 10 years in prison for attempted murder for the injuries, including time served, and to hanging for the murder of the boy.

Speaking with VOA, Senguttuwan’s father, Chandra Segaran, insisted the boy’s death was an accident. He said the banquet area appeared empty when his son mowed into it late at night, also by accident.

According to a news report of the sentencing at the time, the court concluded that Senguttuwan, who was fleeing from police, could not have failed to see people in the banquet area as it was brightly lit.

Chandra Segaran said he supported the end of mandatory death sentencing, and that news of the government’s plans gave him some hope of a lighter sentence for his son.

“Give them prison time, a few years or long-term prison, ok, but don’t hang; it’s a life,” he said.

“Inside the prison they can learn a lesson,” he added. “If you ... hang, in a few seconds he’s gone to death already, so he can’t realize anything. Okay, 20 years. Okay, he killed a person.... He made a mistake, so he can realize.”

Malaysia put an indefinite hold on executions in 2018. But with Senguttuwan’s 10-year prison term for attempted murder nearly up, and his appeals exhausted, Chandra Segaran said he still lives in fear for his son’s life.

Striking a balance

Critics of the death penalty note that most of those on Malaysia’s death row are there for drug offenses — more than two-thirds, according to Amnesty.

Heng Zhi Li is unmoved by the argument.

As an executive committee member of the Malaysian Chinese Association’s youth wing, he joined the campaign against abolishing capital punishment in 2018.

He said he supports this government’s plans to end mandatory death sentencing, but believes judges still need to keep capital punishment as an option in order to help deter the most serious crimes.

Chew, of ADPAN, says the absence of a surge in crimes that carry mandatory death sentencing since the 2018 moratorium argues against capital punishment’s power to deter. Heng ascribes the trend to good policing, and he won’t comment on the alleged flaws in Malaysia’s justice system.

He says leaving capital punishment to the court’s discretion would strike a just balance between the rights of criminals and victims alike.

“Retaining the death penalty doesn’t mean that we ignore the human rights,” he said. “Actually, we are also protecting the human rights of the victims because we have to take into account that ... the victims are being murdered, so what’s the feeling of [their] families?”