Amir Khasru of the VOA Bangla Service contributed to this report.

KRAYEA COMMUNE, KAMPONG THOM PROVINCE, CAMBODIA — The babies are crying, coughing as they vomit.

Each parent holds one of the 8-month-old twins. Their daughters tested positive for the potentially lethal and almost always painful dengue fever.

Lang Chanthoeun says she doesn’t have money yet to get treatment for Pheak Sonisa and Pheak Somatha. “I tried to borrow money from relatives but they didn’t have any,” she said.

“Last night, I couldn’t sleep,” said the 35-year-old mother of six who lives in a poor rural area of Cambodia’s Kampong Thom province on the central lowlands of the Mekong River. The local rubber plantations in the province’s Santuk district shelter mosquitos, making it a center of this year’s dengue outbreak.

A regular cycle of dengue

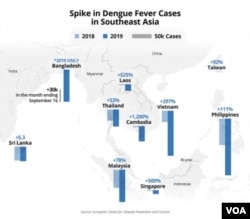

Huy Rekol, director of Cambodia’s National Centre for Parasitology, Entomology and Malaria Control, which is part of the Ministry of Health, said this year’s serious outbreak is part of “a regular cycle of every five to six years or 10 to 12 years” in tropical Asia.

In Cambodia, hard hit during the rainy season that began in May and will not end until October, the treatment for dengue fever can be an enormous burden for poor villagers, who, like Lang Chanthoeun cannot find the money for blood tests and, if found needed, treatment. Some go into debt rather than see family members suffer.

Money or health?

Meas Nee, a political analyst, said that for poor villagers like Lang Chanthoeun, to avoid taking on debt, they need to travel for free care at hospitals like Kantha Bopha in the capital, Phnom Penh, and Siem Reap.

After spending around $35 for her daughters’ blood tests and some medicines at a private clinic, Lang Chanthoeun said she cannot afford to travel for free care. A coconut shell seller, Lang Chanthoeun’s income dried up with the recent unseasonably heavy rains, and the taxi or bus for just one person would cost $10 to $15.

The government should consider providing a treatment center in the province so villagers don’t need to travel, said Meas Nee who holds a doctorate in sociology and international social work from Australia’s La Trobe University.

According to a 2008 article in the International Journal for Equity in Health, “High rates of hospitalization and mortality from dengue fever among infants and children reflect the difficulties that women continue to face in finding sufficient cash in cases of medical emergency, resulting in delays in diagnosis and treatment.”

“Regardless of whether they used a public or private facility, villagers reported spending on average US$34.50 and up to US$150 for a single episode of dengue,” wrote Sokrin Khun and Lenore Manderson in their article, “Poverty, User Fees and Ability to Pay for Health Care for Children with Suspected Dengue in Rural Cambodia.”

In Kampong Thom province’s Krayea commune, many babies and young children have received dengue treatment in local private clinics and from state-run hospitals in the province. A few of them have been treated at the reputable Kantha Bopha Children’s Hospitals in Phnom Penh and Siem Reap.

Both cities are far from Lang Chanthoeun’s rural village, where mothers line up at a private clinic in front of the commune hall. They suspect their children have dengue fever and want their blood tested.

Electricity at the clinic has been cut off because of nationwide shortages thanks to hot weather and the increasing demands from rapidly developing urban centers such as Sihanoukville.

Increasing debt

Pin Roeun is waiting for the results of a blood test for her 8-year-old son, Sok Kea. She said she can pay up to $50 for blood testing, which is usually around $15 to $25, and a short course of treatment.

“I don’t know yet the exact cost,” said Pin Roeun, 38, a farmer who grows cassava while she raises two boys and a girl.

If the cost exceeds $50, she will borrow more money, adding to her current $1,000 debt.

“If I can sell cassava, I can pay the principal,” said Pin Roeun, who had been paying $25 a month in interest on the debt for nearly a year.

Chun Mom, another villager at the clinic, is taking care of her 14-year-old son, Vann Vat, who may have dengue.

A cassava and cashew farmer, Chun Morn said it seems as if there is always somebody in her family who is sick.

“They often get sick like flu, stomach problem,” said the 30-year-old, who is carrying a debt of around $500.

Sun Kimroeun, the Sen Serey Mongkul village chief, said 90% of the 277 families in his village have borrowed money from microfinance institutions and banks.

“Some borrowed money for health treatment,” he said. “They can’t go to work if someone is sick,” he said, adding that most people in his village work at the rubber plantations.

According to the World Bank Group report “Microfinance and Household Welfare,” issued in February 2019, about 4% of borrowers need money to cover health- and injury-related expenses.

On the edge of poverty

Although poverty in Cambodia has fallen sharply in recent years, 4.5 million citizens teeter just above the global poverty line, according to the World Bank.

“The loss of just 1,200 riel (about $0.30) per day in income would throw an estimated 3 million Cambodians back into poverty, doubling the poverty rate to 40 percent,” Neak Samsen, a bank analyst, wrote in 2014.

Cambodia’s GDP per capita was $1,384 in 2017, according to a recent report by two NGOs, the Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (Licadho) and Samakum Teang Tnaut.

Since 2006, the Cambodian government has run a program offering free health care at public facilities. Those who are eligible receive Equity Cards, known colloquially, and predictably, as “poverty cards,” which must be presented to tap into benefits.

But more than a decade after the program began with help from the German and Australian governments, many people remain frustrated and confused about the criteria used to allocate the cards and the benefits bestowed on their holders.

Neither Pin Roeun nor Chun Mom are in the program. That means they don’t have the card for the poorest of the poor.

Lang Chanthoeun said she qualified for the program but has yet to receive a card.

Srey Sin, who heads the Kampong Thom province department of health, said more than three times as many people have shown up at local hospitals for dengue fever treatment in 2019 compared with last year.

“We treat them for free if they have the poverty card,” he said. “Our staffs have tried their best to treat them even though there are a lot of people.”

Lang Chanthoeun’s husband took the twins to a state-run hospital in the province after they were diagnosed with dengue at the local clinic.

Hak Sopheak, 37, said he spent $25 each for treatment of Pheak Sonisa and Pheak Somatha but wasn’t pleased.

“It took my daughters getting worse for the medical staff to get them treatment,” he said. “Before that, they did not receive good care.”