When images beamed back to Earth by NASA’s largest, most powerful space telescope were released earlier this month, U.S. Senator Marco Rubio shared one of them on Twitter accompanied by a Bible verse: “The heavens declare the glory of God.”

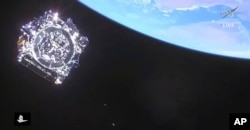

The Webb telescope is orbiting the sun nearly two million kilometers from Earth. The observatory is on a mission to locate the universe’s first galaxies using extremely sensitive infrared cameras. The initial images released to the public provided the first-ever glimpse of ancient galaxies lighting up the sky.

The reaction to Rubio’s post was inundated with remarks like, “You do realize you can only see that due to science?” And, “If only you were scientifically literate enough to understand all of the ways that this image disproves your mythology.”

Reason versus superstition?

The skeptical comments are emblematic of the long-standing, ongoing debate about whether science and religion can be reconciled.

“There are a gazillion religions, each one making a different set of claims about reality, not just about the nature of God, but about history, about miracles, about what happened. And they're all different, so they can’t all be true,” says Jerry A. Coyne, an evolutionary biologist and professor emeritus at the University of Chicago.

Coyne, who likens religion to superstition, wrote a book called, “Faith Versus Fact: Why Science and Religion are Incompatible.”

“The incompatibility is that both science and religion make statements about what is true in the universe,” Coyne says. “Science has a way of verifying them and religion doesn't. So, science is based on this sort of science toolkit of empirical reasoning or duplicating experiments, whereas religion is based on faith.”

Coyne says he was raised a secular Jew and became an atheist as a teenager.

“Scientists are, in general, much less religious than the general public. And the more accomplished you get as a scientist, the less religious you become,” he says.

A 1998 survey found that 93% of the members of the National Academy of Sciences, one of the most prestigious scientific organizations in the U.S., don’t believe in God.

“I personally think there's a couple of reasons for that,” says Kenneth Miller, a devout Roman Catholic and professor of molecular biology, cell biology and biochemistry at Brown University in Rhode Island. “One of them, to be perfectly honest, is the out-and-out hostility that many religious institutions or many religious groups display towards science. And I think that tends to drive people with deep religious faith away from science.”

Mixing science and faith

Some of the world’s foremost scientists have been people of faith, however.

The Big Bang theory, which explains the origins of the universe, was first proposed by a Catholic priest who was also an astronomer and physics professor.

Frances Collins, the former head of the National Institutes of Health who headed the international effort that first mapped the entire human genome, is a one-time atheist who now identifies as an evangelical Christian.

Farouk El-Baz, a professor in the departments of archaeology and electrical and computer engineering at Boston University, says most of his scientific colleagues see no conflict between science and religion. For El-Baz, the son of an Islamic scholar, the marvel of the Webb telescope’s discoveries deepens both.

“Science actually underlines the importance of religion because God told us that He created the Earth and the heavens,” says El-Baz, who is also director of the Center for Remote Sensing at Boston University. “And the heavens, there are supposed to be all kinds of things out there. And scientific investigations have actually proved that, yes, there are all kinds of things out there.”

Evolution, creationism or both

For many, the conflict between science and religion is often rooted in the perceived incongruity between creationism — which suggests that a divine being created Earth and the heavens — and evolution, which holds that living organisms developed over 4.5 billion years.

Miller accepts the theory of evolution and says much of scripture is metaphorical, an explanation of the relationship between Creator and His creation in language that could be understood by people living in a prescientific age.

“[The book of] Genesis, taken literally, is a recent product of certain religious interpretations of scripture,” Miller says. “In particular, it's an interpretation that became quite influential in the latter part of the 19th century among Christian fundamentalists in the United States. And the reality is that much of scripture is figurative rather than literal.”

Jewish tradition also accepts evolution, according to intellectual historian Hava Tirosh-Samuelson, who suggests that the rise of the religious Christian right in the United States also influenced more observant Jews to harden their position against evolution.

“Medieval Jewish philosophy basically followed the Muslim paradigm,” says Tirosh-Samuelson, a professor of history and director of the Center for Jewish Studies at Arizona State University. “The Muslim theologians and the Muslim scholars showed Jews how you can integrate a monotheistic tradition together with Greek and Hellenistic science … and showed how scientific knowledge is always a tool that enables you to understand the divinely created world better.”

Vision of God

In Miller’s view, the concept of God as a designer who worked out every intricate detail of every single living thing is too narrow a vision of the Creator.

“The God that is revealed by evolution is not a God who has to literally tinker with every little piece of trivia in every living organism, but rather a God who created a universe in a world where the very physical conditions of matter and energy were sufficient to accomplish his ends,” Miller says. “And to me, that conception of God creating this extraordinary process that nature itself allows to come about is a much grander vision than a God who has to concern himself with every little detail.”

El-Baz says some people fear that science will reduce their religiosity, but the reverse is true for him.

“We understood through God's guidance that humans evolved from other creatures, and evolution is still going on, and there’s absolutely no conflict between what science and religion are informing us,” he says. “It's very easy to consider that a creator, or a force of creation — God or whatever faith you have — that it's a force that put all of these things together, that created all of this.”

Tirosh-Samuelson says Judaism is not a literalist tradition but rather favors open ended interpretation, which is in keeping with her reaction to the Webb discoveries.

“The grandeur of the universe. The grandeur of God. The grandeur of the human. And in my view, there's no contradiction between those three. On the contrary, there's a lot of complementarity between the three,” she says.

“Jewish culture is really pretty much open to discussion and debate about practically every topic. So, there's something very much in accord with the scientific spirit of inquiry, questioning, uncertainty, skepticism. That's exactly the opposite of a position that is about certainty and rigidity and closed-mindedness.”